CALL TO ACTION

Climate change is without a doubt the greatest challenge humanity has ever faced, and it affects us all. Its indiscriminate nature leaves us wondering what tomorrow will be like. Thinking of our reactions towards this crisis saddens me. Knowing that very little or nothing at all is being done to combat it, while at the same time companies like Total and Shell are opening up fossil fuel industries and oil pipelines around the world. Companies like Coca Cola are producing more plastic every day despite the harm it is causing to our environment and to our health.

I take this moment to applaud us humans. 68% average biodiversity decline in the last 50 years.

750 gigatonnes of carbon a year. At 1.5°C

of warming people are dying – massive floods, droughts, heatwaves, unimaginable hurricanes, lakes drying up, oceans rising, corals drying, ice melting; and yet, we are still comfortable. Global crop failures at 2°C by 2035. Most humans will be dead at 4°C by 2065. Our planet will be uninhabitable at 6°C by 2095.

Dear leaders, your choice of inaction is leading us to extinction. Your choice of inaction and reluctance to combat climate change is affecting the entire planet. We are in a crisis; we are in a climate emergency. Melting glaciers, the arctic is warming, rising temperatures, rising sea levels, flooding, drought. All this and more are what your choices are creating. Your choice to ignore science, your choice to not listen to young voices. Your choice to pretend that you have everything in control, and yet every day of inaction sets us back.

Right now, brand new oil pipelines are opening up. In my country Uganda, the French oil giant Total is constructing the world’s longest heated crude oil pipeline. For many years, groups of indigenous people, corporate organizations, and scientists have talked and warned about the climate crisis, about climate change. This makes me wonder if words from a young man, a victim of the climate crisis from Uganda will make any difference, or if they make any sense to you right now.

Climate change exacerbates existing inequalities in gender, social and health. All these are interconnected and we cannot have one without the other. Climate change is not a generational fight, it’s an intergenerational fight. One which we took on from our grandparents and which we hope to end in our generation, because we are the first generation to know what we are doing and therefore the last to be able to solve it. Future generations deserve better.

Right now, we are suffering the effects of the emissions from our parents, and many people tell us that we do not know what we want. But I want to assure you that the youth of the climate generation know exactly what they want. We youth are organizing globally, we are connecting, we are ambitious, empowered and unstoppable.

In the course of history there comes a time when humanity has to shift to another level of understanding. That time is now. The time for youth inclusion in decision making, planning and action. Because youth-led organizations are providing an invaluable perspective that sometimes policy makers lack.

I am on a mission. A mission to fight for the future. And the voice of the dying youth, displaced, dying animals and distorted nature. I am here to speak for all generations to come. I am not shocked that there isn’t any action taken yet, rather I am in fear. In fear because of the risk, I am taking right now. But the only thing I fear more than climate change is the idea that we youth and people will ever give up on this fight. This is our fight and we have to take on this fight together. Please, leaders and corporations, stop asking us what you can do about the climate crisis, because you know exactly what to do. You know what you are not doing. You know exactly what it takes. So, let’s stop the pretenses, the empty promises, and get to real concrete actions. The world needs change, the world needs change makers. Let’s be the change we want to see in the world. Let’s not wait for miracles to unfold because there won’t be any. Let’s take on this fight as if it was ours, because it is ours. We owe this to our children and grandchildren. Let’s take concrete actions to combat the climate crisis. Together we can do it. This is my plea.

INTRODUCTION

“Climate change is not taking place at an abstract level, but instead is in neighborhoods, in the places youth live and work.”

The climate crisis – the single greatest challenge of our time – is also a crisis multiplier. And Africa, home to the world’s youngest population, stands to be the continent worst impacted by climate change. As the climate crisis exacerbates underlying social, economic, and development challenges, youth will be disproportionately impacted by climate change.

We are on course for these challenges to escalate, especially for youth, as climate change deepens. Unless we take urgent action at the local, national, and global scales, today’s youth and subsequent generations will face increasingly severe climate disruptions that will impact many facets of their lives. This report details the early stages of a worsening situation, explores specific challenges, and proposes some solutions.

The voices of young Africans are often unheard in public and political discussions of climate change impacts, adaptation and mitigation. This reflects various barriers including digital disconnection, poverty, denied visas, and non-existent invitations.10 Yet it is essential that the experiences, insights and recommendations of youth, who already experience climate change in their daily lives, are heard and listened to. This report adds the voices of youth living in Uganda, one of the world’s least developed countries, to the global understandings of climate change adaptation, mitigation, and justice.

Youth face considerable uncertainty concerning work, education, and life prospects. Now combined with the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, the climate crisis is amplifying the development and economic challenges that have faced youth in sub-Saharan Africa for decades. For instance, in Uganda, the collapse of urban job opportunities due to COVID-19 has led many people to make a living from agriculture, while agricultural production has become less reliable due to climate change. Climate change and COVID-19 are layered onto insufficient and insecure job opportunities disrupting the provision of education, and causing further population displacement in a country already impacted by conflict- driven displacements.16,17 These disruptions have immediate impacts and longer-term scarring effects on youth.

CLIMATE CHANGE IN UGANDA

“[By 2100] rainfall will be more frequent and more intense. There will be more floods, more dry spells and dry conditions, and higher evaporation rates so the soils dry out.”

DR. DAVID MFITUMUKIZA, MAKERERE UNIVERSITY

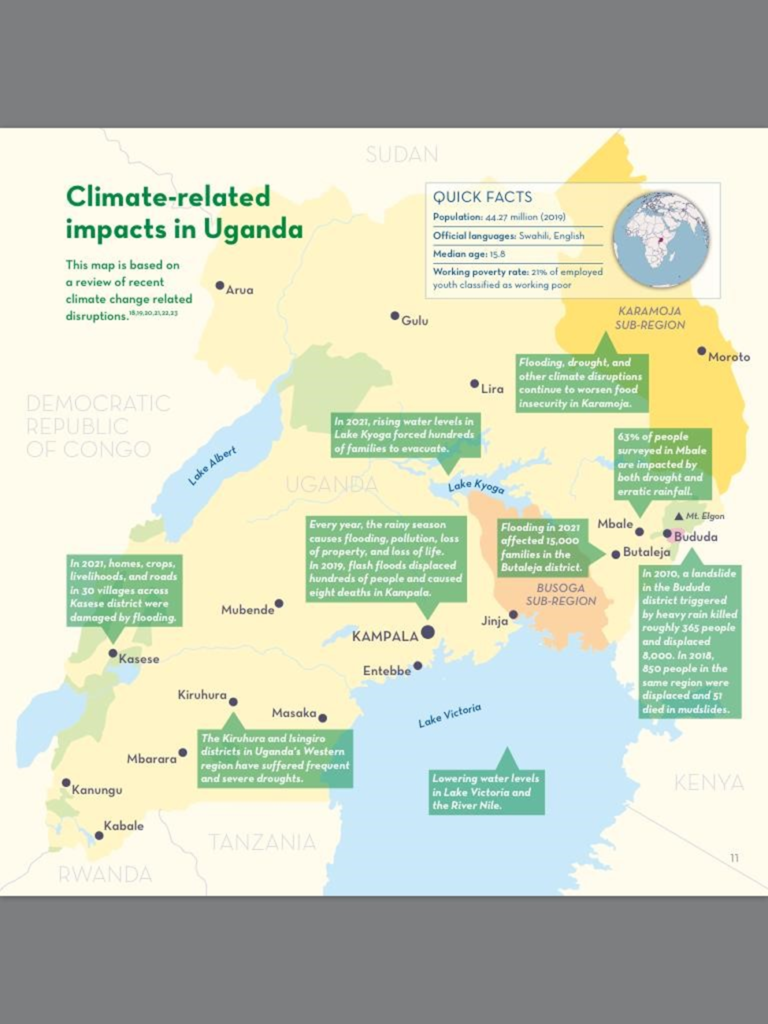

Climate change is already impacting Uganda through both rapid- and slow-onset events (see map on above). In recent years, notable impacts include falling lake and river levels, more frequent and severe droughts, and erratic and excessive rainfall leading to flooding, mudslides and landslides. Exposure to climate risks has been exacerbated by influxes of refugees from neighboring Democratic Republic of Congo, South Sudan and Somalia, with an estimated one and half million refugees now in Uganda. Globally, roughly out of natural disasters can be linked to extreme weather events and climate change, yet a lack of long term and recent data on environmental changes in Uganda, and Eastern Africa more broadly, hampers scientific analysis of past trends, undermining projections. Nevertheless, it is clear that the physical impacts of climate change in Uganda are set to worsen in the coming decades.

Susceptibility to climate change depends upon the nature of physical events, and on the durability of existing economic, political, social, and infrastructural systems. When roads are built without foundations, flood defenses are not constructed, homes are fragile, or weather warning systems inoperative, risk increases. Similarly, a high dependence on agriculture for livelihoods means that single climate events can have long lasting impacts on family health, wealth, income, and nutrition. When families reliant on agricultural production are displaced, they abandon homes, fields, and livestock and may have only meagre funds with which to rebuild their lives. Such families may then be forced to make other difficult decisions, such as removing their children from school or entering their daughters into early marriage.

This chapter focuses on how climate change plays out in the Ugandan context. First, we consider the intersection of climate change and development, then explore a mainstream political and developmental narrative about climate change, and end by reviewing how youth perceive and understand climate change. Overall, this shows a disconnect between the detrimental effects of climate change on development, with some narratives of climate change demonstrating the constrained choices of the most vulnerable youth. Yet many youths have not had the opportunity to learn about the causes and longer-term consequences of climate change, despite experiencing it in their daily lives.

CLIMATE CHANGE AND

DEVELOPMENT

Development and climate change are linked in diverse ways, explains Dr. David Mfitumukiza. Firstly, the disruption and increasing uncertainty associated with environmental changes will impact social and economic development. Secondly, developed countries are responsible for far greater per capita emissions than less developed countries, presently and historically. The Ugandan national pathway to development currently relies on oil, gas and minerals extraction; yet on this path Uganda will continue to contribute to the global climate crisis. This conundrum leads Dr. Mfitumukiza to question ‘is development threatened or is development a threat’ to climate change?

Climate change does not embody a single threat, rather there are many stressors which affect people’s experiences and outcomes. Dr. Mfitumukiza explains:

Agricultural productivity may decline as less predictable seasons make it hard to know when to plant and harvest crops. Furthermore, heavy rains lead to soil erosion and nutrient losses. Low yields may be balanced by extending land under cultivation, resulting in loss of biodiversity and ecosystem services. All this can increase food insecurity; with most (four-fifths) high emissions scenario models projecting declining rice production.

We plant and then the rain washes away what we plant. Recently we received little rain, which means it is hard to plant rice as it dries out. Youth cannot go to school because not enough was earned from selling rice, and then there are early marriages too. People get frustrated because rice is not working, but without an alternative to go to.

Water shortages, excessive rainfall and flooding are highly disruptive, compromising water quality and raising the risk of outbreaks of waterborne diseases. Insufficient water (and siltation from erosion) can also disrupt household and agricultural water use, and compromise the hydroelectricity production upon which Uganda depends.

Thirdly, ‘development and adaptation deficits’ are likely to lead to conflicts and forced migration.

In Uganda, we need to not only focus on how climate change is affecting agriculture, and turn our lenses to the other side of the coin… as long as there is no alternative source of livelihood, or the appreciation of sustainable approaches to agriculture, questions raised by communities will continue to come in the form of ‘What other chance do we have for survival?’

Climate change threatens Uganda’s social and economic development on multiple fronts. Dr. Mfitumukiza emphasizes the need to build capacity and resilience to better confront climate change. Local governments should roll out climate change policies which engage the close linkages between climate change mitigation and poverty reduction. In fact, adaptation and mitigation are complementary goals rather than separate agendas. A good example of this is afforestation, which creates a carbon sink while stabilizing water supplies and acting as a windbreak. Dr. Mfitumukiza reminds us that while adaptation is especially important for Uganda, it is important not to lose sight of climate change mitigation.

RESEARCH DATA INSIGHTS

What comes into your mind when someone talks about climate change?

“Rain is good but when it over rains, for us who work on the shores, the rain affects us. Because on my side of the work place you would find a lot of water flooding inside. Now the sun is shining, but when you

find this place on a rainy season, it’s a disaster. Rain affects us as you see in this area, you can’t walk in this place when it rains. That is why we wear boots. Our feet are always in the boots; you can’t live in this

community without boots because you would become sick, your feet will swell. The climate changes affect us strongly.”

26-YEAR-OLD WOMAN FROM A PERI-URBAN COMMUNITY IN JINJA

CLIMATE CHANGE NARRATIVES

A pervasive charcoal-climate-youth narrative promoted by NGOs and current policy agendas shows an interpretation of charcoal production that demonstrates and criminalizes poor rural communities, explains Dr. Adam Branch. Moreover, the narrative offers little climate change mitigation, and diverts attention from the industrial actors behind large-scale deforestation. This narrative runs as follows.

- Charcoal is a dirty energy source and is being replaced by gas and oil. In fact, charcoal is the primary energy source in 90% of households. Fuel switching to electricity is not happening so there is a need to work with charcoal and not against it.

- Charcoal production is driving deforestation and climate change. However, facts about biomass energy are not well known. In Uganda, charcoal is blamed for climate change despite its low carbon footprint compared with many other energy sources.

- Charcoal is produced by rural youth who exploit shared resources, due to desperation, greed, or a lack of environmental concern. The idea that youth are the primary drivers of destructive charcoal production is false – most damage is caused by large industrial work crews clearcutting entire forests.

- Finally, there is a need to halt charcoal production. Halting production impacts marginalized people more severely than the elites. Small-scale and vulnerable households who rely on charcoal production for their livelihoods are worst impacted by its criminalization. We need to be careful about identifying the causes of climate change and promote environmental justice, concludes Dr. Branch. Environmental justice must build upon the understanding that the rural poor sell charcoal due to poverty, precarity and unemployment. Socially responsible responses to climate change would enable poor people to still make a living. Dr. Branch warns how climate change can “be used to justify interventions which are not good for the poor or the environment”, proposing that “policy should start with youth activism and struggle for environmentalism and energy justice”.

CLIMATE CHANGE

AWARENESS

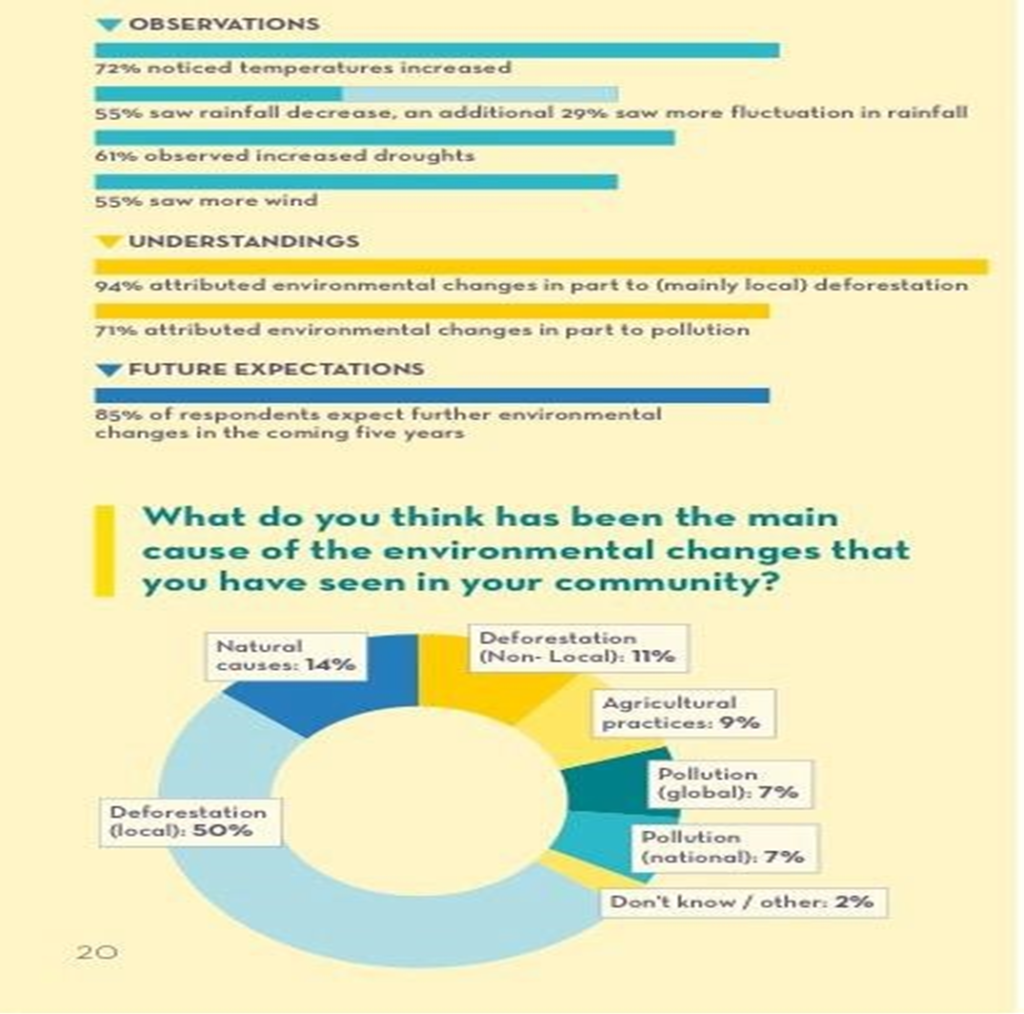

Adding to existing science and policy understandings of climate change, our primary research investigated youth’s experiences and knowledge of climate change. Most of the youth surveyed had observed environmental changes during the past five years, particularly increased temperatures and droughts, with changes to rainfall too, and stronger winds. The primary driver of these changes is understood to be local deforestation, followed by natural causes. More than four-fifths (84%) of respondents expected more environmental change in the next five years.

Despite these tangible changes, the survey responses indicate an information vacuum. Around three-quarters (74%) lacked access to adequate information about how the environment is changing; nearly two-thirds (64%) did not know where to get meteorological forecasts which could warn of extreme events; and over half (57%) did not know where to find information on how to respond and adapt to climate change. This information deficit means that while youth experience and have to respond to climate change in very immediate ways, they are doing this with little guidance, or understanding as to why they are facing these challenges. Moving forwards, the local and indigenous knowledge of youth and their elders should be incorporated into wider understandings of the consequences and solutions to anthropogenic climate change. While the intensity and frequency of climate disruption is new, the experience of responding to prolonged drought and food insecurity is not. These strands of understanding need to be woven into media reporting on climate change, new school curricula, vocational training, and policy.

RECOMMENDATIONS

- More environmental data are needed to enable scientific analysis and future climate predictions for Uganda and neighboring countries.

- Future policies should take into account the interconnections between climate change and poverty.

- Mitigation and adaptation should be seen as connected and complementary.

- Caution is needed around the charcoal- climate-youth narrative given its tangible and damaging effects.

- Policies should build upon environmentalism and energy justice.

- More reliable climate change information is needed in the media and through schools – this should detail the causes of climate change, pathways to mitigation, local weather and climate change warnings, and advise on immediate responses and longer-term adaptation. Local people understand change in climate, not in the scientific research, but from the way they are directly affected in the seasons.

RICHARD HAMBA, EBAFOSA (UNEP)

CLIMATE CHANGE IMPACTS ON YOUTH

“Climate change is increasing poverty levels in Uganda… [with] effects like school dropouts, early marriages, increased diseases, increased violence, malnutrition, increased

unemployment…”

The consequences of climate change for youth in the developing world run the gamut from the economic to the emotional. Such impacts include disrupted livelihoods and climate-related displacement, and also disrupted education, nutritional deficits in youth and children, and anxiety and other mental health challenges. Uganda is one of the world’s youngest countries, with a median age of just 15.8.39 Uganda’s youthful population, who are still building the social and economic capital of older generations, are likely to bear the brunt of climate-related disruptions. Moreover, youth around the world have suffered from increased uncertainty and higher unemployment rates as a result of the worldwide economic downturn linked to the COVID-19 pandemic. This section discusses the way that climate change affects the lives of youth in Uganda and offers recommendations for how individuals, households, communities and other national or international actors can mitigate climate disruptions.

LIVELIHOODS

Agriculture is a vital source of income for youth in Uganda and across Eastern Africa, many of whom are engaged in low-productivity employment in smallholder agriculture. Historically, farmers in Uganda have been able to profit from two growing seasons a year – March to May and September to November. However, variability in weather and rainfall has put pressure on agricultural production by shortening the growing season and reducing predictability. One young Ugandan reported that “There has been a change in seasons. Due to these climate changes these days, people [are only able to] plant in one season”.

The negative impacts of climate change are not limited to rural areas – in urban areas, youth seeking to sell food or other goods contend with increasingly dusty conditions during dry seasons and flooding in rainy seasons. Some youth in my research had their offices and workshops damaged by flood waters, while brewers and carpenters reported how flooding disrupts the production and transportation of their raw.

The combination of low household incomes and a deficit of social protection means that many people diversify their incomes by engaging in a multitude of economic activities. As climate change continues to impact agriculture in Uganda, youth continue to seek alternative livelihood. For example, some youths are turning to boda boda (motorcycle taxi) driving or poultry farming as an alternative source of income, though these activities are not immune from climate change disruptions. Overall, a disproportionate number of youths are employed in the informal sector, underemployed, or jobless, so are particularly vulnerable to economic downturns and the disruptive economic impacts of climate change.

DISPLACEMENT

Climate-related displacements in Uganda and elsewhere are driving people from their homes, compromising livelihoods and weakening or severing social ties. Climate-driven displacements include

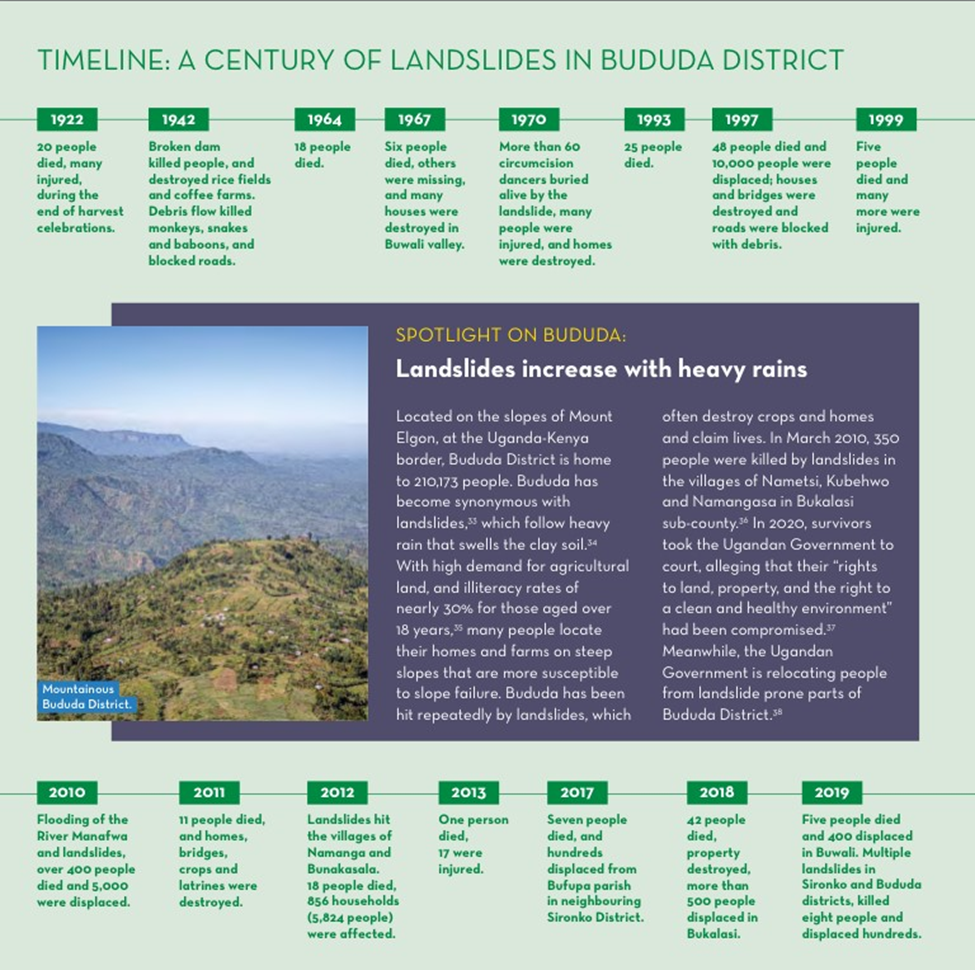

the movement of people due to slow- or rapid-onset weather events, voluntary migration to mitigate risk, and planned relocation (such as from Bududa district)

Although rapid-onset events make headlines, it is slow onset changes that are likely to spur the majority of climate-related migration flows. To give a sense of scale, globally, in 2020 roughly 26,900 children were forced to leave home as a result of weather-related events every day. The past decade has seen weather-related internal displacement overtake conflict-driven displacement in Uganda.

In Eastern Africa, a major cause of migration is the region’s increasingly long and frequent slowonset droughts. Nevertheless, in Uganda rapid-onset flooding and landslide events have driven hundreds of thousands of people from their homes. Recent floods in Karamoja damaged roads and bridges, destroyed homes

and businesses, and swept away the livestock upon which pastoralists depend. The loss of one’s home, land, business, or livestock can be economically and emotionally devastating, pushing some to rebuild their lives in a new place.

EDUCATION

One consequence of climate change disruptions and displacements is interruptions to education. UNICEF UK’s Anja Nielsen explains that disrupted education has short- and long-term impacts on children and young adults, including on their educational attainment and future economic opportunities. Moreover, climate-related disruption to education does not occur in a vacuum, but adds to an existing education crisis in which globally millions of children are already out of school and roughly half of the children living in low- and middle-income countries are not able to read a basic story by the age of ten.49 There is also an issue of education sometimes seeming irrelevant, as one interviewee explained:

“Most youths don’t have jobs; some have degrees but don’t have jobs. They are always on the lakeside, dirty, carrying passengers to the boats yet the parents

spend a lot of money educating them. So, I have realized that I won’t educate my child because even the ones educated lack jobs.”

26-YEAR-OLD MALE MECHANIC, JINJA

Although the threats that climate change poses for education are serious, education can also strengthen awareness of, and responses to, climate change. Many workshop participants highlighted the need for increased climate change and environmental education in schools, beginning at the primary level. Education has an important role to play as a mechanism for knowledge and capacity building.

One workshop participant suggested that climate change education be localized, so that students and community members can learn about and be prepared for the climate disruptions that may affect their own localities. Another attendee suggested that older students would benefit from training and skills development focused on climate adaptation and mitigation. Youth in Karamoja want to learn more about climate change, in order to understand weather patterns and gain knowledge about local adaptations to climate disruptions.

RESEARCH INSIGHTS

Climate change losses

Youth often associate the impacts of climate change with loss – loss of livelihoods, of agricultural produce, of lives, or of natural resources.

A young respondent from Jinja stated that: “A youth would put up a temporary canteen made out of

wood and make a small business so that they can be able survive, but now the waters from the

lake come and destroy and they are displaced, sweeping away all these small houses.” Recovering from such losses is an enormous challenge for

most youth. Damage to infrastructure such as houses, shops and markets was found to be more prominent in Jinja, whereas respondents from the Karamoja sub-region reported suffering more damage to property and livestock due to floods.

Anxiety about climate change

The eco-anxiety of many youths should relay a strong message to world leaders about the importance of combating climate change. A respondent from Jinja lamented that:

“In the coming times… people may face a [year with] no season, or a disorganized season structure which will confuse farmers and lead to drastic changes in food production. The more we delay, the more the problems will continue, and even worsen”.

Other youth highlighted that climate change is happening right now: “I am worried about the environmental changes in the future because we are already experiencing them. I am more

worried about the indirect impacts we will see.”

Climate conflicts are currently on the rise in Eastern Africa. A young respondent from a pastoralist community in Uganda’s north- eastern said: “Raids, insecurity, diseases, hunger… These are the effects that make me most anxious because they will lead to a loss of lives and livelihoods…”

Youth also lack government support. One respondent said that “When these impacts happen, the Government does not come to help, and we are facing many losses”. Another respondent called for support to ease climate conflicts and help communities to coexist peacefully.

MENTAL HEALTH

Many youths feel anxious or hopeless about climate change. Workshop discussions emphasized the harmful effects of climate change on the mental health of youth in Uganda. Youth experience devastating impacts from climate change as jobs, homes and families are lost – impacts which have been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Negative mental health outcomes include Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, anxiety, and depression. Moreover, mental health services are often inadequate.

The enormity of climate change can seem overwhelming. Many youths frame the climate crisis in pessimistic terms and feel that they lack the agency and influence to address the multifaceted challenges of climate change.51 Youth employ a variety of coping mechanisms to deal with these negative feelings, including de-emphasizing the seriousness of the climate crisis, seeking to distance themselves from negative emotion, and problem- focused strategies.52 Problem-focused strategies include seeking out information, taking direct action to address climate change, and working to raise the awareness of others.53 Such strategies channel anxiety or stress about the climate crisis into positive action.

This can be supported by engaging youth in climate mitigation and policy discourse at all levels. 49% of respondents felt that they had no control or ability to influence climate change.

RESEARCH INSIGHTS

Rising living costs

In peri-urban and rural communities, youth endure numerous direct effects of climate change on their livelihood activities due to their extensive dependence on natural resources. It is commonly perceived that youth in urban communities do not face many of these direct effects yet declining supply of food and natural resources with reduced agricultural productivity inflate food prices. Urban dwellers are also directly impacted by extreme weather.

A young woman in rural Jinja described how “climate change has led to poverty because of too much rain. People won’t go to work, and we can’t transport our goods to the market – for example, today most youth are not going to work because of this rain, which affects the income of the

youth in the community.”

For a demographic that is especially vulnerable to shocks and stressors, a worsening climate crisis is stretching their resilience, pushing a generation to the brink of poverty.

The need for jobs is pressing. One interviewee explained that “Many youths in this community

lack jobs due to the disasters that occurred in this community.”

FOOD INSECURITY

A major risk of climate change in Uganda is worsening food insecurity. Food insecurity exists when people are unable to access sufficient safe, nutritious food.54 As climate disruptions continue to impact agriculture and economic growth, increasing numbers of people will struggle to purchase food – a problem that may be compounded by rising food prices.55 Sub-Saharan Africa as a whole is one of the regions of the world most vulnerable to climate-related food insecurity.56

The 2020 Global Hunger Index rated food insecurity in Uganda as “serious”, and the World Food Programme has highlighted concerns about acute food and nutrition insecurity in several districts of the Karamoja sub- region.57 Youth there reported increased food and water shortages, with these shortages leading to higher food prices and compounding the risk of food insecurity by imperiling the ability of households both to grow and to purchase food. Climate shocks such as drought and flooding can lead to reduced food consumption and increased poverty levels.58 Recent flooding in the Karamoja region is likely to exacerbate food insecurity. 57% of respondents were concerned that climate change will have a strong and direct impact on them, their friends, and their families.

RECOMMENDATIONS

- There is a continued need to engage and listen to youth in climate change discussions.

- Environmental education can empower youth to understand climate change and respond. This education must be relevant to youth’s own communities, with actions that can feasibly be taken at the individual, household, and community level.

- Youth would benefit practically and psychologically from support for problem-focused activities such as raising awareness, taking concrete action in their own lives, and engaging in climate policy debates.

- There is a continued need for job creation in order to offer reliable income streams which can buffer against some climate change impacts.

- Job finding support and training will become increasingly important as large numbers of youth continue to leave traditional agricultural production and migrate to urban or periurban areas.

YOUTH RESPONSES: ADAPTATIONS & ACTIVISM

Climate change is already happening, so through necessity youth are responding. Youth responses include making adjustments to daily behaviors, reducing individual-level environmental impacts, actively participating in tree planting programmes and other green agendas, and engaging in political activism to advocate for systematic change. Youth’s responses to climate change thus fall along a wide spectrum, from activists at the global level, to those active in their communities, those seeking to fortify their own livelihoods or support their families, to those who are not at all proactively responding.

Many youths are not equipped with the social, financial, or political capital needed to adapt to climate disruptions. Indeed, more than two-thirds (69%) of the youth surveyed reported that they were not adapting to environmental changes. This may be as a result of their limited resources, or feelings of hopelessness, a perceived lack of agency in climate discourse and policy making, or limited awareness of climate change adaptation strategies.

At the other end of the spectrum, global youth climate activism movements like Fridays-ForFuture have attracted widespread attention from politicians, policymakers, and ordinary citizens alike. Many youths in Uganda are inspired by and participate in climate justice movements. Amongst them, high profile Ugandan climate justice activists Hilda Flavia Nakabuye and Vanessa Nakate connect to international youth climate networks while also engaging in grassroots activism.

This chapter highlights the responses of youth in Uganda, both in their own lives and as part of broader activist movements and awareness raising campaigns. Moreover, the chapter outlines the challenges that youths face in their efforts to mitigate the impacts of climate disruption on their own lives and to make real change to politics and policy. This section also briefly outlines some gaps in current mitigation strategies and recommends steps that can be taken by individuals, communities, and other actors to address these challenges.

31% of respondents have adapted their livelihoods in response to environmental changes.

These adaptations include increasing irrigation by hand, planting trees, diversifying crops, leaving their villages, starting brewing or brick making, starting businesses, and sharing environmental messages.

During rainy seasons I create water paths to redirect water away from the community I stay in. I have involved my neighbors in creating water channels to avoid floods from accumulating within our areas, now most of the community members are doing the same to minimize floods.

28-YEAR-OLD BRICK LAYER AND BODA BODA DRIVER, NAWAIKOROT RESPONSES

Many of the steps that young adults in Uganda have taken to adapt to climate disruptions in their own lives center on day-to-day shifts and adaptations at the household level. During the Kampala-Cambridge workshop, participants highlighted an array of ways that youth reduce climate impacts on their lives and in their communities. Many youths are leaving agricultural production, seeking to diversify their income by engaging in the informal sector to generate income. Some activities also contributed to climate change mitigation, such as recycling materials or promoting cleaner cooking stoves. Derrick Mugisha explained how youth turn used plastic into earrings, necklaces, bracelets, and other crafts; which has a low environmental impact while offering a new income stream to young craftspeople.

Some youths have diversified their income sources to build resilience to climate change disruptions to agricultural livelihoods. One example is shifting away from sugar cane, which is highly vulnerable to climate disruptions, and finding crops that are more resistant to heat and drought. Some households diversify their income streams to include poultry farming or beekeeping. Youth have also sought out livelihoods beyond agriculture. In Uganda, popular alternatives include sports betting, selling food or other goods in urban areas, and driving motorcycle taxis.

The adoption and use of eco-friendly energy sources such as charcoal briquettes are making its way into youth’s homes. Youth in Busoga’s urban communities are learning to recycle and produce their own sustainable energy sources as an alternative to cutting down trees. These are some of the initiatives that must be supported and scaled up to cultivate a wider positive impact and permanent switch to clean energy in surrounding communities.

In addition to seeking out ways to support themselves and their families, youth are also engaging in many activities related to directly combating climate change and raising awareness about the global climate crisis. Many youths in Uganda are active in youth-mobilization groups, climate activism movements, NGOs, and other organizations that seek to promote awareness of climate change and foster climate mitigation activities.

BARRIERS TO CHANGE

Youth typically lack the financial and material resources needed for major climate adaptation, and are not well represented in high-level policy and business discourses on climate change. Many of the youth interviewed over the course of my research expressed hopelessness and anxiety, feeling that they had limited ability to drive meaningful, large-scale change. Similarly, many youths identify a lack of systemic, organized support (financial and otherwise) for youth and communities affected by climate change.

The individual and household adaptation strategies that many young Ugandans have already employed or are likely to rely on in the future are inadequate to meet the challenges of climate change – particularly when such disruptions are likely to worsen in the future. To support and empower youth with climate mitigation and adaptations, both big and small, it is vital youth receive education, training, and financial support.

RESEARCH INSIGHTS Obstacles to activism

Recognizing the direct and indirect impacts environmental changes today will have on their futures, youth are demonstrating a strong willingness and commitment to address climate issues. But before they can take any community action; they must overcome their fears of authority and build their self-esteem to contribute to meaningful change.

“My only challenge is the authorities. I am young, I cannot tell someone mature that what you are doing by cutting the tree is bad”, stated one of the respondents. Another young person expressed that “the hostile political atmosphere in the country has barred my activities as an activist.” Pathways to change

A young respondent implores us to: “Imagine climate change as though it is a wound on the planet. Educating people about climate change is the most effective treatment that can be

applied for this wound to heal.”

Human activities and daily habits are difficult to change, but the climate crisis demands immediate responses: “The truth is that many people are not educated and are ignorant about environmental conservation.”

Climate education is an important intervention with the ability to catalyze a faster, large scale collective response to climate change. Climate education would enable people to understand the causes and consequences of climate change, which can empower them to support adaptation. Education is a critical gap that continues to widen even as various stakeholders are working to address climate issues across

Uganda. A young respondent we spoke to hinted that although NGOs are addressing climate change through different interventions: “they have not engaged youth or encouraged them to take part in climate activism. Their focus has mostly been on older adults”.

Youth must be prioritized in climate related interventions, especially climate education, as they will face worsening climate change impacts in the near future.

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Youth need access to financial resources to adapt to climate change. This could involve financing youth-led climate initiatives and the innovations of young activists and entrepreneurs.

- Climate discourse and education must be inclusive. Educational or skills- building materials need to be relevant and translated into a wider range of languages to make them accessible to some of the most marginalized youth.

- Integrating climate change education into school curricula would engage youth who are currently excluded from climate change discussions.

- Activists, NGOs, governments and businesses must work together to amplify the voices of youth. Currently, the exclusion of youth from political and policy making circles blunts their potential, contributing to feelings of powerlessness.

GREEN JOBS

“COVID-19 fiscal recovery packages have typically not been green, nor have they sufficiently

targeted youth.”

Existing social and economic insecurities amplify the new uncertainties wrought by climate change, and so require decisive policy and labor market responses. The challenge is to address both social and environmental issues – concurrently promoting adaptation, mitigation and resilience. The rationale for this integrated approach is threefold. Firstly, vulnerability to the adverse effects of climate change increases with poverty. Secondly, the creation of decent, wellpaid jobs offers a route out of poverty, thereby increasing resilience to climate change. Finally, new work opportunities could bring additional environmental benefits if these new jobs are green jobs.

Green jobs contribute to the preservation or restoration of the environment. This impact might be achieved through enhancing efficiency to reduce the consumption of energy and raw materials, limiting waste and pollution, protecting ecosystems, reducing greenhouse gas emissions, or enabling climate change adaptation. Green jobs thus include a broad range of occupations and activities. Some green jobs can be grown within existing sectors such as construction and in new sectors such as renewable energy.60 Of course some caveats surround this idealized solution. In particular, new jobs should be ‘decent’ and inclusive – meaning that they pay living wages for safe work, convey legal and social protection, and recognize workers’ voices.61,62 Ideally these jobs will promote the creation of a low impact, circular infrastructure which minimizes the environmental impact of new consumption.

Green jobs fall into a wider policy ambit that also includes broader responses to climate change, youth, and development and addresses key questions about the future of energy (including the relative balance of oil, hydro, solar, and biomass) and who will be the winners and losers in any transition. Historically, poorer people have often lost out in major economic transitions. A just transition would actively reduce inequalities, ensuring the outcomes for the world’s most vulnerable people improve the fastest.

Here we share insights from the Kampala-Cambridge workshop. Although the youth interviewed and surveyed in my research said little about green jobs specifically (the green jobs discourse often focuses on urban elites), many workshop participants demonstrated a strong interest in what green jobs could mean in practice in Uganda. Young research participants shared what they want from policy makers in response to climate change. This chapter concludes with green jobs recommendations from the workshop discussions and wider policy recommendations stemming from my research findings.

NEW GREEN JOBS

Kee Beom Kim notes that the green economy constitutes one of five economic sectors that are key to a job rich recovery from COVID-19 for youth. The others are the blue economy, creative economy, digital economy and care economy. In global terms,

a transition to energy sustainability could create 25 million new jobs gross (while 7 million jobs could be lost). A circular economy transition could create 78 million jobs gross (while 71 million are lost).63 This transition will require coordination between ministries, and the provision of social protection for people displaced by climate change or unable to find new work.64 Spending choices must address immediate needs and also enable a just transition.

Georginah Namuyomba explained that in Uganda there is great potential for green job creation in agriculture because it is the ‘backbone of the Ugandan economy’ and the main employment sector for rural youth. Within agriculture, some circular economy practices are well established, such as using manure to fertilise crops. However, various barriers persist for those seeking to fund or develop green jobs. One such challenge is the lack of a legal framework to reassure lenders that debts will be repaid; another challenge is identifying new green jobs with the most potential in the Ugandan context.

Two examples of green businesses follow.

GREEN BUSINESSES

Green Heat – renewable energy

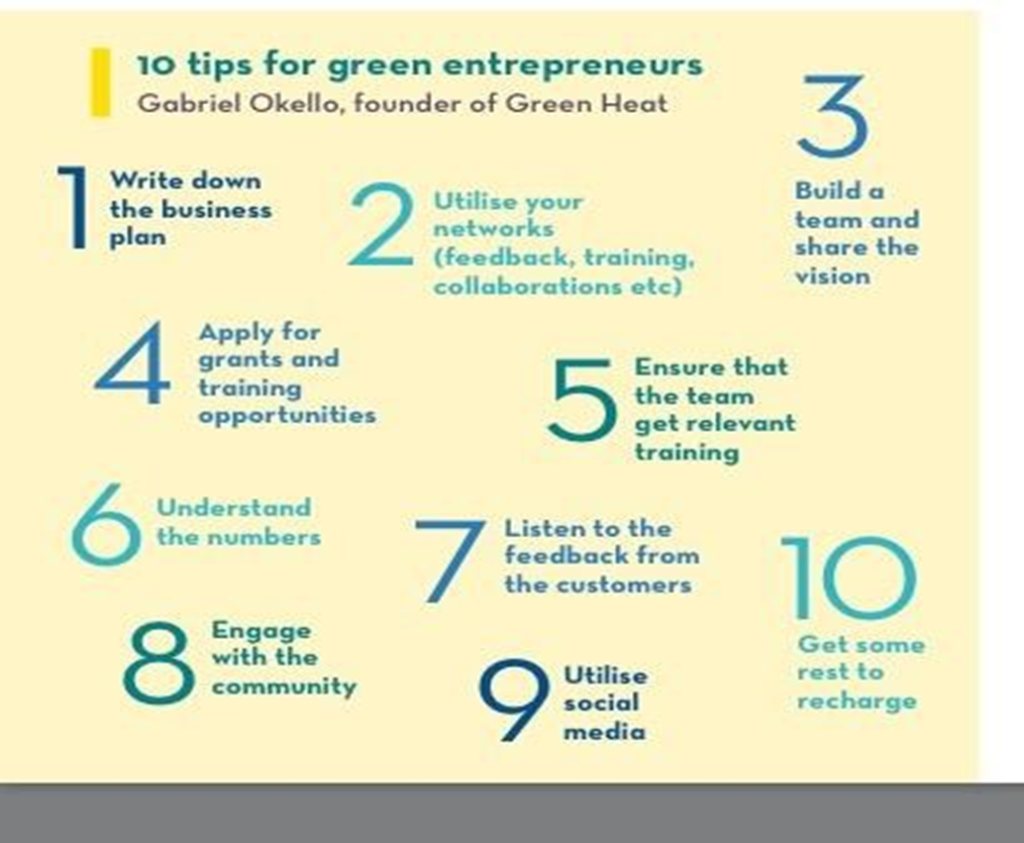

At the workshop Gabriel Okello described setting up biogas and charcoal briquettes business, Green Heat, to offer clean cooking technology. Where he grew up in East Uganda, everyone cooked using firewood but at university he learnt about cleaner cooking fuel. Alternative sources of fuel increase access to fuel availability, support waste management in the community, and slow deforestation. Gabriel encountered various challenges including access to capital, both to start up and scale-up, and the issues of a small team needing to cover all the skills needed for a business. Team well-being suffered because of high work demands, and Gabriel sometimes worked 15-hour days. Gabriel shares advice for young green entrepreneurs (see above).

Eco Brixs – circular economy plastics

Eco Brixs, located in Masaka, recycles plastic waste into durable products such as bricks, fencing posts, benches, paving slabs, and visors. Each month as many as 3,000 people in the local community bring plastic for recycling – creating a green income stream for many disadvantaged local people. Furthermore, Eco Brixs employs 13 full time staff. Currently, they collect 30 tonnes of plastic a month – processing six tonnes at their plant in Masaka and exporting the rest. Removing plastic from the local environment and processing it safely reduces river, soil, and air pollution.65

Plastics recycling is a viable green job in Uganda because of very many tonnes of plastics available. Which green jobs are most favourable for youth in Busoga growing districts like Jinja, Luuka and Mauyuge, as they are trying to shift from sugarcane?

MBEIZA PEACE, YOUTH

NEXT STEPS

Learning and training are top priorities to enable a green transition. Current teaching on climate change does not give children an adequate understanding of what climate change is, why it is happening, or how mitigation responses work. Incorporating climate change learning into school curricula from primary school onwards would equip youth to understand climate change. Furthermore, training in the particular skills needed for green jobs is vital. Such skills could be taught in vocational schools. Education and training are essential for building skills and capacity, while simultaneously sensitising youth to the issues of climate change.

The costs of setting up and running green businesses can be prohibitive. As a result, many workshop recommendations pivoted around making green jobs economically viable – especially via government grants subsidies, and tax relief. In particular, reducing the costs of solar power and biogas technology, subsidising machinery and equipment, and financial support for education and training would help. Such interventions must sit within a wider employment programme that prioritises sustainability and promotes social and development imperatives, offsetting the economic risk associated with green job creation.

Youth are critical to growing green jobs in Uganda. Many youths, early in their working lives, are open to new opportunities so are well positioned to transition into green jobs. This process must extend beyond urban elites to reach poorer people and those living in rural areas, and work will be required to maximise the accessibility of training, and not rely on digital provision. Furthermore, given the large informal economy in Uganda, any move towards green job creation must engage the informal sector. It will be important to involve youth in policy conversations, and to incorporate their job aspirations into the next round of policies and policy implementation.

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Climate change education should begin at primary school, followed by green jobs skills training opportunities for youth.

- Build a supportive policy environment to incentivise and finance green job creation, and to handle the legalities, monitoring and evaluation.

- Inclusive approaches, involving diverse youth, will generate stronger understanding of the issues and enable tailored, sector-specific solutions.

- A strong dialogue is needed between youth, government, business and international donors.

- A platform is needed to connect, learn, share and be heard.

CONCLUSIONS & RECOMMENDATIONS

“I would like to see that my response to this research makes an impact and brings change.” This report shares new insights into how youth experience and adapt to climate change in Uganda, one of the least developed and youngest countries, on the continent set to be most affected by climate change. The goal of this report is to amplify the voices, insights, and recommendations of vulnerable, highly-impacted youth in the global conversation about the nature of climate change. By creating space for their voices in climate change discourse, we discover the obstacles that youth face, how they are already responding to climate change, and their demands for the future. It is well established that the experiences, needs, and wishes of the so-called beneficiaries, as offered in this report, must be taken into account when designing effective policy.

This report is evidence-based and future facing. My research and workshop, which engaged more than 1350 youth in 2021, took place in the context of ongoing disruptions due to climate change and the COVID-19 pandemic. Even in a zero emissions scenario, climate change will continue because of the greenhouse gases that have already accumulated in the atmosphere.66 As a result, our findings speak not only of the challenges that youth already face, but also those to come in a future defined by the global climate crisis.

As climate change imperils agricultural production, increasing numbers of youth will seek alternative livelihoods in the informal economy or migrate to urban and peri-urban areas. Food and water shortages and higher food prices threaten further food insecurity and childhood malnutrition in Uganda, and especially in the Karamoja region, which is already an area of particular concern to the World Food Programme. Millions of people are displaced every year by slow and sudden-onset climate events. In Uganda, worsening droughts and severe flooding are threatening the lives and livelihoods of many families. Climate change induced displacement and poverty can disrupt children’s education, harming their wellbeing and their economic prospects, and adding to the historical challenge of enabling education for all.

Youth are not passive in response to climate change. Some relocate, diversify income streams, or tweak their livelihoods to build resilience. Others may have fewer options, or lack the resources to invest in new training, work or business ventures. Feelings of powerlessness, along with the strong sense of loss that climate change brings, can present a bleak outlook

for youth. A few make practical and political interventions such as tree planting (to store carbon and improve the local environment), and climate activism (to raise awareness and spur political and business responses). Fridays-For-Future Uganda, as part of a global network of youth climate activism, campaigns for three goals. First, to keep the global temperature rise below 1.5 °C compared to pre-industrial levels. Second, to ensure climate justice and equity. Third, to listen to the best united science currently available.67

Much wider responses are needed that engage youth, including those who are poorer, more vulnerable and/or hard to reach. Having learnt from youth about what they want and need, it is necessary to mobilize the power of policy, business, finance and the international community to strengthen responses to climate change in respect of both mitigation and adaptation. The urgency and scale of the challenge demand action.

Climate action and adaptation must simultaneously address inequalities, poverty, and the jobs deficit, and support the most vulnerable. At times, responses to climate change can be misaligned, for instance the charcoal-climate-youth narrative in which the most vulnerable are misconstrued and demonized as drivers of climate change and suffer from increasingly constrained livelihood options as a result.

What follows are two sets of recommendations. The first set comes from youth and is directed at political leaders; the second is a synthesis of the youth-led research and a youth-focused workshop.

RECOMMENDATIONS-FROM YOUTH TO POLITICAL LEADERS

- Secure education and jobs.

Many youths’ education is cut short due to financial constraints; this could be addressed with scholarships or free education. Large scale job creation is needed to provide reliable incomes and good career prospects.

- Strengthen agriculture.

Farming is badly hit by climate unpredictability, yet irrigation systems and drought resistant crops could increase climate change resilience.

- End hunger. Many people already go hungry and this may worsen as climate disruption increases. Food insecurity must end.

- Prevent embezzlement.

Sometimes funds do not reach their targets due to embezzlement, so greater financial accountability is needed.

- Stop exploitation. There is a lack of transparency and accountability amongst large companies, for instance in the mining sector, and local monopolies often control resources.

This unequal power, weak transparency, and preferential resource access must end.

- Build infrastructure.

Infrastructure is sometimes damaged by flooding, blocking transport routes and damaging property. Strong roads, water storage, and drainage ditches are needed, so that rainwater can be channeled away from infrastructure. Water could also be saved from wet spells and used in dry spells.

- Plant trees. Land and property are damaged by strong winds and flooding. Trees can offer protection. Although we need access to the local trees from our area to plant, we cannot find them.

- Provide training and startup capital. There is a lack of resources and funding to support more climate resilient livelihoods. Training and start-up capital are needed so youth can diversify their livelihood options (such as carpentry, poultry farming, chapati making, mechanics, and small shops).

RECOMMENDATIONS-FOR POLITICIANS, BUSINESS, AND THE INTERNATIONAL

COMMUNITY

- Inclusive dialogue for fairer outcomes. Strong dialogue is needed between young people, government, business and international donors. With an inclusive and accessible platform to connect, learn, share and amplify, such dialogue would amplify the voices of disadvantaged youth, and enable learning about policy needs and outcomes.

- Education and training. Starting at primary school, environmental education is needed to empower youth to understand and respond to climate change. Later, green skills training should be relevant to youth’s own lives and communities, with actions they can feasibly undertake.

- Information sharing. More reliable climate change information is needed in the media and through schools – this

should detail the causes of climate change, pathways to mitigation, local weather and climate change warnings, and advice on immediate responses and longer-term adaptation.

- More and better data. More environmental and meteorological data are needed to enable scientific analysis and future climate predictions for Uganda and neighboring countries. Longitudinal social science data are needed to continue to document and understand the ongoing impacts and support policy makers to design well- informed policies.

- Green job creation. Job creation must be stepped up to provide reliable income to buffer against climate change disruption; green jobs can be boosted by green skills training, startup capital, and a supportive policy environment.

- Cut greenhouse gas emissions. We are on track for more climate change and disruption, yet to prevent it being much worse there is a great urgency to reduce global greenhouse gas emissions. Adaptation should be built into mitigation interventions, as they are complementary and some interventions can achieve both.

- Increase financial support.

Accessible financial support and financing initiatives are key to enable youth to make adaptations to their own lives. Youth also need greater financial resources that will empower them to respond to climate change in their communities and home countries, and on international stages.

REFERENCES

- Met Office. 2001. What is climate change? https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/weather/climate– change/what-is-climate-change

- United Nations Climate Change. No date. Kyoto Protocol – Targets for the first commitment period. https://unfccc.int/process– and-meetings/the-kyoto-protocol/what-is-the- kyotoprotocol/kyoto-protocol-targets-for-the- first-commitment-period

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. 2021. Least Developed

Countries. https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/ least-developed-country-category.html 4. UNFCCC. Climate Action Pathway: Climate Resilience. https://unfccc.int/climate–action/ marrakech-partnership/reporting-tracking/ pathways/resilience-climate-action-pathway 5. The Republic of Uganda. 2001. The National Youth Policy: A vision for the 21st Century, Ministry of Gender, Labour and Social Development. 6. United Nations. 2021. Climate Change ‘Biggest Threat Modern Humans Have Ever Faced’. United Nations Press Release SC/14445. 23 February 2021. https://www.

un.org/press/en/2021/sc14445.doc.htm 7. Gates, B. 2018. The world’s youngest continent. The blog of Bill Gates. https://www.gatesnotes.com/Development/ Africa-the-Youngest-Continent

- African Development Bank. 2021. Climate change in Africa. https://www.afdb.org/en/ cop25/climate-change-africa

- Barford, A., Proefke, R., Mugeere, A. and Stocking, B., 2021. Young people and climate change. COP 26 Briefing Series of The British Academy, p.1-17. doi:10.5871/ bacop26/9780856726606.001.

- Barford, A. 2021. Climate talks will fail without more young people’s voices. World Economic Forum Agenda. 3 June 2021. https:// www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/06/whyclimate– change-summits-need-young-peoples-voices/

- Barford, A., and Nyiraneza, M. 2021. Young activists are tired of their views on the climate crisis being ignored. The Independent. 11 August 2021. https://www.independent.co.uk/ climatechange/opinion/climate-crisis-uganda- young-activists-cop26-b1896067.html

- Barford, A. and Coombe, R. 2019. Getting by: young people’s working lives. Published by Murray Edwards College, in April 2019. CC BY Creative Commons license. 10.17863/

CAM.39460 https://www.repository.cam.ac.uk/ handle/1810/292310

- The Independent. 2021. Experts call for Ugandan youths to grasp opportunities in agriculture to confront pandemic. 6 September 2021. https://www.independent. co.ug/experts-call-forugandan-youths-to- grasp-opportunities-in-agriculture-to-confront- pandemic/

- ILO. World Employment and Social Outlook: Trends 2020. Geneva, CH: ILO, 2020. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/– –dgreports/—dcomm/—publ/documents/ publication/wcms_734455.pdf.

- Barford, A., Coutts, A., and Sahai, G.. forthcoming. Youth Employment in Times of COVID.

International Labour Organisation.

- UNICEF. 2021. Futures at Risk: Protecting the Rights of Children on the Move in a Changing Climate. London, UK: United Nations Children’s Fund United Kingdom. 17. Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre. 2021. Uganda. https://www.internal– displacement.org/countries/uganda

18. Davies, R. 2021. Uganda – Severe Flooding Affects Thousands in Butaleja. Floodlist. 19. Muhumuza, M., Muzinduki, P., and Hyeroba, G. (2011). Small holder farmers’ knowledge and adaptation to climate change in the Rwenzori region. A research journal of the Rwenzori

Think Tank Initiative, 117-133

- Nagasha, J., Mugisha, L., & Kaase-Bwanga, E. (2019). Effect of climate change on gender roles among communities surrounding Lake Mburo National Park, Uganda, Emerald

Open Research, https://doi.org/10.12688/ emeraldopenres.12953.2

- Oxfam 2017, in Oriangi, G., Albrecht, F., Dibaldassarre, G., Bamutaze, Y., Isolo Mukwaya, P., Ardö, J., & Pilesjö, P. (2020). Household resilience to climate change hazards in Uganda.

International Journal of Climate Change Strategies and Management, 12(1), 59-73.

https://doi.org/10.1108/ IJCCSM-10-2018-0069

- Daily Monitor, 2019. Over 30 people feared dead in fresh Bududa mudslide.

- Uganda Red Cross Society. 2021. Latest News.

- Chambers, R. 2014. Rural development: Putting the last first. Routledge.

- Mugeere, A., Barford, A., & Magimbi, P.. (forthcoming). “Climate change and young people in Uganda: a literature review”. Journal of Environment and Development.

- Mugyenyi, O., Mugeere, A., & Amumpiire, A., A. (2020). Conserving the Environment and Enhancing Community Resilience: The Key Climate Change Priorities during and after COVID19, Kampala: ACODE, Policy Briefing Paper Series No.53.

- Chirambo, D. Enhancing climate change resilience through microfinance: Redefining the climate finance paradigm to promote inclusive growth in Africa. Journal of Developing Societies

33, 150–173 (2017). DOI: 10.1177/0169796X17692474

- IPCC, 2021: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

[Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S. L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M. I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J. B. R. Matthews, T. K. Maycock,

T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu and B. Zhou (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press.

- Toulmin, C. (2009). Climate change in Africa. Zed Books, London.

- Kunreuther H., S. Gupta, V. Bosetti, R. Cooke, V. Dutt, M. Ha-Duong, H. Held, J. LlanesRegueiro, A. Patt, E. Shittu, and E. Weber, 2014: Integrated Risk and Uncertainty Assessment of Climate Change Response Policies. Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change.

Contribution of Working Group III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Edenhofer, O., R. Pichs-Madruga, Y. Sokona, E. Farahani, S. Kadner, K. Seyboth, A. Adler, I. Baum, S. Brunner, P. Eickemeier, B. Kriemann, J. Savolainen, S.

Schlömer, C. von Stechow,

T. Zwickel and J.C. Minx (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

31. World Bank, 2021: Climate-Smart Agriculture. https://www.worldbank.org/en/ topic/climate-smart-agriculture 32. UNICEF. 2021. Futures at Risk, 27.

- Ekotu, J. J. (2012). Landslide hazards: Household vulnerability, Resilience and Coping in Bududa District, Eastern Uganda. Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Masters in Disaster Management in the Disaster Management Training and Education Centre for Africa at the University of the Free State, South Africa.

- Knapen, A., Kitutu, M.G., Poesen, J., Breugelmans, W., Deckers, J. & Muwanga, A. (2006). Landslides in a densely populated county at the foot slopes of Mount Elgon Uganda, Characteristics and causal factors, Geomorphology, 73:(1-2), 149-165.

- Uganda Bureau Of Statistics (UBOS). (2017). National Population and Housing Census 2014. Area Specific Profiles. Bududa District.

- Kitutu, K.M.G. (2010). Landslide occurrences in the hilly areas of Bududa District in Eastern Uganda and their causes. Unpublished PhD thesis. Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda. 37. Client Earth. 2020. Bududa landslide victims take Ugandan Government to court. Press release. No page. https://www.clientearth.org/latest/press–office/ press/bududa-landslide-victimstake-ugandan- government-to-court/ 22 October 2020.

- Watala, P. 2019. More than 140 Bududa landslide families to be relocated to Bunambutye camp. Relief web. https://reliefweb.int/report/uganda/more- 140-bududa-landslide-families-berelocated- bunambutye-camp

- Statista, 2021, African countries with the lowest median age as of 2021. Original data source not stated. https://www.statista.com/ statistics/1121264/median-age-in-africa-by- county/ 40. Nordås, H.K. “COVID-19 and globalisation: a poverty perspective on tourism and remittances”, Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (May 2020): 1-5. http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep25728.

41, 42. ILO, World Employment: Trends 2020, 42.

- ILO, World Employment: Trends 2020, 35.

- Barford, A. et al.. 2021. Young People and Climate Change, London, UK: The British

Academy. 10

- Nielsen, Anja and Rose Allen. Futures at Risk: Protecting the Rights of Children on the

Move in a Changing Climate. London, UK: United Nations Children’s Fund United Kingdom,

2021. 5

- Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre. 2021. Uganda. https://www.internal-

displacement.org/countries/uganda

- Anna Barford et al. Young People and Climate Change, 11

- Anna Barford and Charles Mankhwazi. 2021. How young people in Uganda are living the climate crisis. Newton Fund-GCRF Data Insights. https://www.newton-gcrf.org/impact/ datainsights-blog/how-young-people-in- uganda-are-living-the-climate-crisis/ 49. UNICEF, Futures at Risk, 7. 50. Barford et a., “Young People”, 8.

51. Maria Ojala, “Eco-anxiety”, RSA Journal, vol. 164, no. 4 (2018), pp. 10-15, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26798430.

52, 53. Ojala, “Eco-anxiety”, 12.

54. FAO, “Food security: concepts and measurement,”, Trade Reforms and Food Security, 25-

34. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2003.

55. David Mfitumukiza, 2021. Climate Change and the Development of Uganda. Keynote lecture, at the Kampala-Cambridge Workshop 2021: Young people, climate disruption & adaptation in Africa. 12th July 2021, online. 56. Global Hunger Index (GHI), “Global Hunger Index 2020”, https://www.globalhungerindex.

org/ranking.html. 57. WFP, Uganda Country Brief May 2021 58. Barford et al., “Young People”, 5 & 9.

- Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre. Uganda.

- ILO, 2016. What is a green job? https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/green-jobs/ news/WCMS_220248/lang–en/index.htm

- Barford, A. and Ahmad, S.R., 2021. A Call for a Socially Restorative Circular Economy: Waste Pickers in the Recycled Plastics Supply Chain. Circular Economy and Sustainability, p.122. doi:10.1007/s43615-021-00056-7.

- ILO. 2021. Decent work. https://www.ilo.org/ global/topics/decent-work/lang–en/index.htm 63. ILO. 2019. Skills for a greener future: a global view. https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/ decent-work/lang–en/index.htm, 24. 64. ILO. 2019. Skills for a greener future.

65. Re-circulating plastic. RE:TV. 2021. https:// www.re-tv.org/rebalance/recirculating-plastic 66. NASA. 2021. Is it too late to prevent climate change? https://climate.nasa.gov/faq/16/is-it- too-late-to-prevent-climate-change/

67. FridaysForFuture. 2019. Our demands: rom the Declaration of Lausanne, on August 2019, agreed by 400 climate activists from 38 countries. https://fridaysforfuture.org/what-we- do/ourdemands/

RESEARCHER: MUKISA ELIJAH DARLINGTON

AGE:19 YEARS

GENDER: MALE

NATIONALITY: UGANDAN